Editors Note: This article concerns the various mall proposals in Katy between The Grand Parkway and Mason along I-10. These proposals were made over almost 40 years, with no one plan ever coming fully to pass.

Williamsburg Mall was a planned regional mall for the Williamsburg Master Planned community in Katy, Texas. The original idea for the mall and most of the community were abandoned years ago, but a few pieces of the original ideas have come to pass years later. A large portion of the original development now houses Katy Asia Town. It all began In 1973, when Houston developer Marvin Leggett and a group of associates purchased a 2600-acre plot of former farmland along I-10, just outside of Katy’s city limits. Leggett planned to build the first modern planned community on Houston’s fast-growing West Side to complement the planned Park Ten development adjacent to it. The promise of both Park Ten becoming a second downtown and the bordering Mason Road becoming the Grand Parkway, Houston’s next planned loop, were both tremendous selling points. The neighborhood would be split into multiple sections, with home prices ranging from $30,000- $300.000; the most expensive homes would sit around a man-made lake large enough to warrant a marina. In addition to the mall, medium and small shopping centers were planned throughout the community, and room was even left for warehouses and a distribution center. However, the development of the ambitious project stalled during the 1973 oil crisis, with the land sitting vacant until 1977. After the economy had rebounded, development would once again pick up, with the first homes starting construction that year. Only a few months later, mall building giant DeBartolo announced their plans to enter Houston with the construction of the Williamsburg Mall. DeBartolo had purchased a 115-acre parcel from Leggett at the Southeast Corner of the Williamsburg development, which was part of a larger 270-acre section reserved for retail.

While it’s not confirmed how word of the mall spread to national developers, it was likely Legett had shopped his land to multiple mall builders. In the time it had taken Legett to select DeBartolo as his partner, two other major developers had made their way to the intersection. Mall giant Sears had purchased over 200 acres at the Southeast Corner through its Homart division, which built malls. On the Northeast Corner, local developers Wolff Morgan & Co had purchased a 100-acre lot and planned to build a mall with Kravo, a developer best known for King of Prussia Mall or, more locally, Ridgmar Mall in Fort Worth. Wolff Morgan and Kravco were also supposedly building another mall further up I-10 at Highway 6 as part of Park Ten. It was intended to be a second Galleria, and their Katy Mall was to be of a lesser status. Only a few months after this initial announcement, Homart would make good on their plans and announced the new Meadowbrook Mall was to join the slate of new *-brook (Deerbrook, Willowbrook, Baybrook) malls being developed around town. Kravco would still get mentions in passing, but their failure to produce any updates by the end of 1980 cast doubts on their projects, including potential malls in San Antonio. In 1981, Kravco would quietly pull out of the Texas projects it was working on. While the remaining two malls would reduce their scope to help balance each other out. The ideas seemed concrete; Homart and Debartolo had avoided mutually assured destruction, and both soon began preliminary work. Homart would start by deed restricting its property, and DeBartolo began looking for contractors to bring basic infrastructure to the

Williamsburg site, which was already zoned for their needs. However, in the short span from 1978 to 1980, development all but stopped not just in the malls but also in the residential portion of Williamsburg. Less than a quarter of the planned neighborhood had been built out, and none of the aforementioned lake or marina seemed to even be on the books by 1980.

In the background, larger issues were calling for big shifts in planning in 1978, shortly before DeBartolo signed on to build the mall; the Grand Parkway was “officially canceled” as part of the late 70s freeway revolts. It wasn’t the first time a road had been canceled in Houston, and in general, most canceled projects came back to life when demand called for it; as such, developers continued to promote Mason Road as the future route of the Grand Parkway. However, it was this very promotion that was causing the issue. Only a very short stretch of Mason had been constructed by the 1980s, extending a few miles North and South of I-10, including a large overpass for the planned parkway. While TxDOT had acquired land adjacent to Williamsburg, the land North of the planned route was left to be developed. The 1980s oil glut also had largely stalled work on Park Ten and, according to real estate experts, hampered Williamsburg’s chance at success. While work would eventually start again on homes in the area, the mall would remain untouched. On the other side of the freeway, though, Homart had shifted its work to a complex named Mason Park, which was meant to complement the mall. It provided shopping centers and a movie theater while leaving room close to the freeway for the future mall, with the first sections opening in 1982. The Williamsburg Mall was mostly silent but was said to still be underway by DeBartolo in 1984. In 1985, Coldwell Banker, which had invested in the property, gave an expected start date of 1987. Although before any of this could happen, Marvin Leggett passed away in May 1985. While Leggett’s firm would continue the project, they didn’t seem to have the same grand dream he had envisioned. In 1986, DeBartolo dropped out of the project and sold 110 acres of their site to Homart to allow them to take over Williamsburg Mall. Homart wouldn’t provide a start date but did say they were planning on Sears, Ward’s Penney’s, Joske’s, Lord & Taylor, and either Foley’s or Macy’s as prospective anchors. With this new land, all work on Meadowbrook Mall would be halted; by this point, the mall had been whittled down to 300,000 Square Feet and would have likely only had Sears and one other anchor, in addition to a small number of inline shops.

With Homart in charge, Williamsburg Mall had a prospective tenant list for the first time, and development in the area was reaching an all-time high. It seemed like the mall was a sure thing. However, like every year prior, the mall simply failed to get off the ground. While Homart did not completely abandon the area, continuing to expand Mason Park, and seemed to plan on building the mall. However, the last update from Homart came in 1987, which stated that the mall was still underway but didn’t elaborate. At the time, Homart had their hands in multiple malls in the Houston area, and this would not be the only one they quietly abandoned. The property would remain in the hands of Homart until about 1994, when FirstBanc, who had taken control of the rest of the undeveloped neighborhood, purchased the property about a year before Homart was dissolved. The future looked unsure for Williamsburg Mall and the neighborhood as a whole. A strip of land between the two residential sections was completely untouched, causing a discontinuous feeling. The land sat directly North of a divided boulevard, the main entrance to Williamsburg, originally named Peek Road. While it was obvious there was intent to extend this road, the open patch North of it was quite wider than the boulevard. This division was created after TxDOT quietly brought the Grand Parkway back to life in the 1990s. To avoid the development along Mason, TxDOT eyed the grand entrance planned for Williamsburg, which was to meet up with Peek Road to the North. Selling this land likely cemented the end to the lakes and marina for Williamsburg and would also scare off developers. The state would go so far as to purchase extra land on both sides of the freeway for a planned interchange that would not be constructed for about 20 years. With the master-planned community now split in two, a company named Interfin Corp. purchased 727 acres of the original Williamsburg development, mainly on the East side of the Parkway. The large plot of land was a mix of residential and commercial land, including the proposed plot for Williamsburg Mall. Interfin, which was headed by Giorgio Borlenghi, developer of Uptown Park, mentioned they felt an expectation came with them purchasing this site to build the mall. However, their first priority was to build a power center facing the Interstate. Internfin later clarified that the mall may or may not use the Williamsburg name, but their plans for the property likely wouldn’t resemble a traditional mall, which he said would be on the way out. While Interfin wouldn’t provide many details on the coming plans, the first official work on the Williamsburg Mall would start in 1996, specifically infrastructure work to finally bring power, water, and sewer to the corner of the otherwise untouched land.

With the new positioning of the Grand Parkway, the mall site was moved to the southwest corner of Interfin’s property, once again butting up to the Grand Parkway and I-10. While things looked promising, work would again stall out. However, unlike previous malls, in early 1997, an update was provided on what was happening. It turned out that the Mills Corp. had been negotiating with Interfin to potentially use the Williamsburg site for their proposed Katy Mills Mall. The Mills Corp had even signed an option to purchase the site but would eventually back out due to roadway access issues. During this time, a new roadway issue had cropped up. The South side of the potential mall was unsure as TxDOT had purchased the former MKT railroad that ran along it and was planning a big expansion of I-10. Various design proposals had different ideas for this land, from maintaining the railroad and building passenger stations to running a tollway along the land adjacent but separate from I-10. This huge undertaking would directly affect the planned mall property, and again, the development would mostly stall. However, one small bit of progress came the following year when Borlenghi signed on with Cinemark to build a new Tinsletown theater on the property to replace their old theater in Mason Park. After construction on the movie theater began, another company named Chelsea CGA Realty announced their plans to build the Houston Premium Outlets on the Williamsburg site. Chelsea CGA had developed the Premium Outlets concept, which was quite popular. It was essentially the first concept to build a truly high-end and luxurious outlet mall. These plans looked extremely promising as more and more Premium Outlets Malls were opening nationwide, including one in DFW. Houston seemed a logical next step for Chelsea, and Katy doubly so.

However, things took an odd turn when a Rhode Island-based developer named Commonwealth announced they were planning a competing mall across from Williamsburg. This newest mall, simply called the Commonwealth Mall, was proclaimed to be a Foley’s-type center, but they wouldn’t provide much beyond that. While Katy had grown substantially since the last time three malls were simultaneously proposed in the area, even then, it was obvious to real estate analysts that Katy would not be able to support that kind of traffic even in the near future. However, none of the three developers did much in the way of acknowledging that Elephant was in the room, except for Chelsea/CGA. They doubled down on the Houston Premium Outlets, saying they didn’t believe three malls would ever be built, calling Katy Mills a fluke, and refusing to acknowledge the Commonwealth Mall seriously. The company boldly stated we would not announce this project if we didn’t intend to proceed. Commonwealth was a relatively new mall builder and had been limited to Massachusetts and Rhode Island in its short existence, but it did manage to build some impressively difficult malls like Providence Place Mall, a massive high-end downtown mall that opened in 1999 after years of development hell. While the snub from Chelsea/CGA and the lack of acknowledgment from the Mills Corp seemed harsh, the reality was Commonwealth was likely in over their heads. It seems that the 200 or so acres the company had purchased for their mall was split across The Grand Parkway. While the company likely was aware of this, it’s easy to imagine that they could not envision the access issues, construction, and interchange that were to follow. Commonwealth would quietly sell its property only about a year after purchase.

The plan for the Houston Premium Outlets largely resembled other Premium Outlets built by Chelsea CGA before and after this plan. Basically, it was an assortment of high-end outlets (Coach Outlet, Nike Outlet, etc.), with off-price versions of high-end retailers (Sak’s Off 5th, Neiman Marcus Last Call, etc.) serving as anchors. While we know this concept quite well today in Houston, it was completely foreign at the time, with our outlet malls generally being strip center-based and usually geared towards the lower end. Neiman Marcus Last Call was the first retailer to publically sign on to HPO, giving them a leg up against Katy Mills, whose first tenants would not be revealed for another few months. Around this time, DeBartolo, which had merged with fellow mall giant Simon, suddenly became interested in the project again. Agreeing to an equal partnership with Chelsea/CGA, Simon DeBartolo bought into Houston Premium outlets. While this would not be their first alliance, this purchase would set up the death of what was likely the most promising version of this property. While this was not the first partnership Chelsea and Simon had entered into, finally scheduling a groundbreaking after their agreement, there were legal issues afloat. The Mills Corp had been watching the nearby situation and was unhappy with what it considered unfair competition. In August 1998, Mills sued Simon DeBartolo for a breach of contract. Mills had worked with Simon before and signed contracts that, going forward, each company would allow the other first right of refusal in nearby competing projects. Mills contended that Simon should have offered them a steak in HPO when they signed on. Simon, on the other hand, argued the projects were different enough that they wouldn’t compete. As construction had yet to start, ideas such as shrinking the mall to invalidate the old contracts were floated. However, less than a month after the lawsuit, Chealsea CGA accepted a buyout from the Mills Corp for their half of the property. With Chelsea CGA exiting the deal and the Houston Premium Outlets name gone, the project was put on hiatus with only the Cinemark open and operating. Mills Corp. and Simon agreed to develop the land, but not as an outlet mall. In 2004, long after the dust from HPO had settled, Neiman Marcus Last Call would move into Katy Mills.

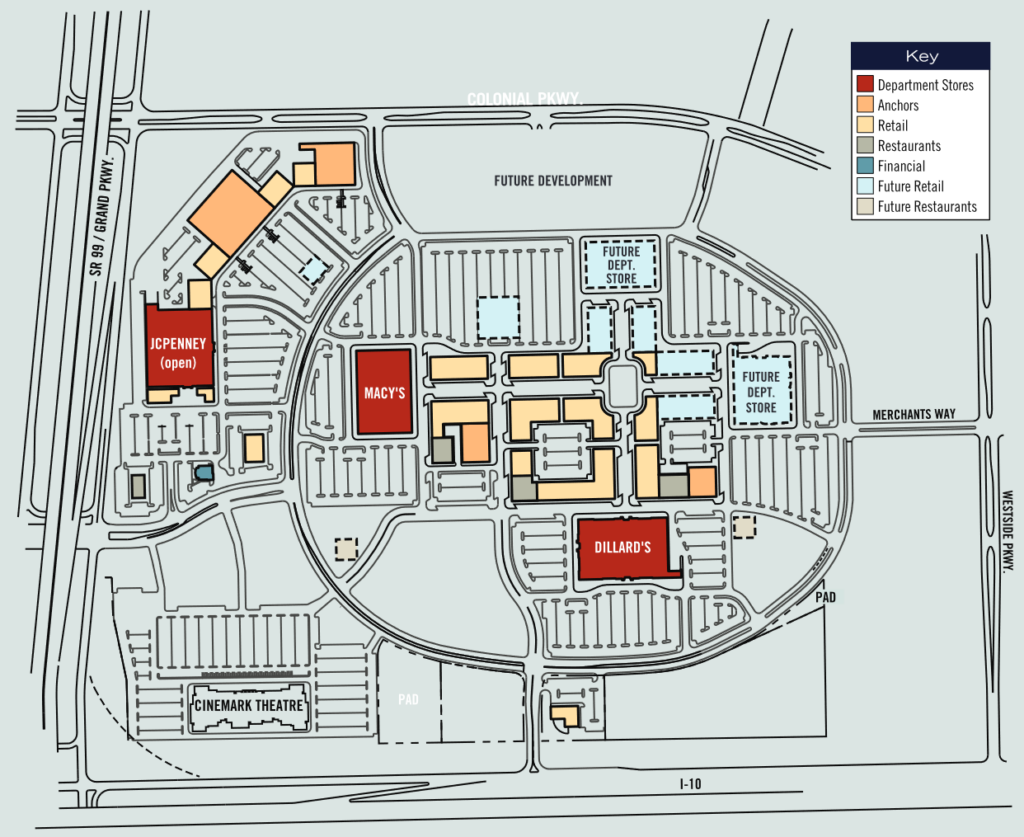

In 2001, Simon and Mills announced plans for a traditional regional, four-anchor mall, much like Marvin Legett had envisioned in the 1970s. This new mall, christened “West Houston Mall,” would include Dillards and Foley’s. These two confirmed anchors were being lured from West Oaks, and this threat was one of the reasons for West Oaks’ early 2000s remodel. The West Houston Mall was meant to attract whatever customers Katy Mills didn’t, drying up West Oaks’ Westside customers. It would have four anchors and come at over 1 Million Square Feet to compete. Interfin was still involved, and with Simon’s strong commitment, they began the first real development the mall had ever seen. Their master plan called for implementing many original Williamsburg ideas, including the mall and more retail along the highway, along with filling in more of the Williamsburg residential development, including a series of small lakes. They even donated land to build a high school to encourage more residential development. By 2002, the mall was starting development with Interfin bringing utilities in the middle of the site and starting a ring road, allowing access to the property from I-10, The Grand Parkway, or Colonial Parkway. Although all the roads only led to Tinsletown, early steps for a mall were finally set in motion. However, as quickly as progress started, Simon’s vision began to drift. The indoor mall would quietly be modified into an outdoor Lifestyle Center by about 2003. It was likely influenced by the only other large-scale shopping center with real prospects in Houston at the time, Pearland Town Center. By this point, the mall had signed on all of West Oak’s main anchors, with Macy’s and Dillard’s being quite upfront about their involvement and JCPenney and Sears being ratted out by the press. However, Simon wanted to go for a more upscale look, booting JCP and ending the deal with Sears by 2004. JCP would be allowed to anchor an adjacent power center next to the mall named “The Grand Promenade.” At the time, no other tenants had signed on to build the Grand Promenade, and JCP’s store would sit by itself for nearly ten years. This newest version of the mall would also receive a new name, “The Grand.”

This future mall sat on a road named Grand Circle, which was likely a play on the nearby Grand Parkway. However, Simon chose to lean completely toward this idea of grandeur with The Grand. The reason for JCP’s demotion was to facilitate room for two upscale department stores, later revealed to be Nordstrom and Neiman Marcus. While it was never confirmed that these were the two stores signed, Simon seemed to have dropped these names when talking to business owners in the area. Going in this new direction and borrowing ideas from the Chelsea/CGA plans also allowed The Mills Corp. to exit the picture, with Simon buying out their shares and Mills happily accepting the much-needed cash for stuck projects of its own. The delay in attracting these new upscale stores pushed back the construction dates, which were finally announced as starting in 2006. Construction was to be split into two phases, with phase one consisting of the “main mall,” specifically Dillard’s and Macy’s (Foley’s), and traditional mall boutiques making up about 75% of the space. The second phase was the luxury phase, which would feature the two high-end department stores and the rest of the inline shops, which were to be luxury brands. The announcement was enough to kickstart a small amount of construction on a few restaurant lots, along with Dick’s Sporting Goods making plans to join the JCPenney in the now-renamed “West” Grand Promenade. This renaming seems related to Simon’s planning for another portion of the power center along the mall’s north side. Katy was once again rapidly growing, and everything looked quite promising for The Grand to work out. While it wouldn’t be a traditional mall, essentially all the normal mall elements would be included. Some concepts even included a food court, a holdover from the Chelsea/CGA Simon Debartolo plans. Although around this time, as if they were a canary in a coal mine, Interfin sold lots of its mall adjacent property, including the Cinemark, to Newquest. Still, the ring road around the planned mall would be completed in 2007 before development would once again stall out. Community members would draw comparisons between the proposed mall and nearby failed Town & Country due to its proximity to an under-construction interchange and competing mall. However, something completely different behind the scenes sealed the mall’s fate.

In early 2007, The Mills Corp was put up for sale after years of financial troubles. Initially, Canadian developer Brookfield stepped up to purchase the ailing Mills. However, Simon provided a more substantial offer. By April 2007, Katy Mills Mall had quietly become a Simon Mall, meaning The Grand would be directly competing with a mall now in their own company. They also had signed on more tenants like Barnes & Noble and Old Navy. Katy Mills had a Books a Million and Old Navy Outlet, putting the two malls truly in the same boat. While Simon would maintain the facade that it would build the mall as intended, stating it would open by 2012, in the background, they would ponder their next move. The recent years had been rough, and with many businesses not making it through the Great Financial Crisis of the late 2000s, Simon essentially gave up on the plan to build a mall. While Katy was continuing to grow, even during a rough era, Simon’s now international presence in what was a depressed market of malls meant that the only reasonable action for them at the time was to axe the project. Their first option was to go back to Interfin and see if they wanted the property back, which the company immediately rejected. Even with some development around the West Grand Promenade, including Newquest prepping the land in front of Cinemark, Simon could not sell the land until 2014, when Park Capital purchased the vacant land from Simon. The property, which included everything inside of the Mall’s circle, the remainder of the West Grand Promenade, and the undeveloped Grand Promenade, along with a few pad sites, was to be redeveloped as Verde Parc. This would again spark more development in Houston’s first Whiskey Cake, and a few other restaurants joined Verde Parc. Although beyond these individual lots, no master plan seemed to reach the public. While it does appear that one was developed and looked to make mixed use of the property, the interest of UH in the land hindered further development.

In 2016, the mall parcel was split in half, with the top portion being sold by UH and options being given for some along the bottom. Adjacent pieces were also sold off, with some going to Newquest and others going to private developers who have since built Katy Asian Town on the land. Newquest has focused on expanding on the entertainment venue concept it bought into with the purchase of the Cinemark and uses the name Katy Grand, specifically attaching it to a large parking garage they built for carpool users in conjunction with METRO. Newquest has also used a portion of the mall land to build retail, most of which hosts Asian tenants. UH opened a Katy satellite campus on their land in 2019 and is said to be soon starting development on more buildings on the property. Katy Asian Town has easily become the dominant draw to the property, with new business springing up in what was to be the West and original Grand Promenade areas. Development on the east side of the property remains sparse, with apartments and a business park taking up much of the space of the very first proposal for the Williamsburg Mall in the SE corner of Marvin Legett’s original purchase. Over 50 years after discussion of a mall began for this site, it’s safe to say one will not be built. While it does have elements of original plans, JCPenney and Cinemark, and the Grand Circle ring road being the most notable, none of the original plans have worked out. Even mid-2000s hopeful Dick’s sporting goods abandoned the project for a nearby shopping center. Leaving one to wonder what really killed this mall. Was it the location? Was it the proximity to Katy Mills? Was it the wrong concept for the area? In the end, I think it all falls down to mismanagement. While Katy Mills does fine for the area, with the neighborhoods North of Katy growing along 99, it does make you wonder where the next mall will be. While Williamsburg/Meadowbrook/Houston Premium Outlets/West Houston Mall/The Grand would have been a perfect site, its future is sealed in development.